INFOCUS: Agriculture — Groundwater depletion

Ranjit Singh Ghuman

The Punjab Government has at last acknowledged that reckless abuse of groundwater, non-harvesting of rainwater and wheat-paddy crop rotation would result in desertification of the state in the next 15-20 years. However, given the track record of successive governments in Punjab, there is little hope that the problem will be addressed in an effective and sustainable manner. For the past about four decades, governments conveniently ignored the ever-growing problem of water scarcity in Punjab. They refused to read what was written on the wall. The only significant step taken to save groundwater was the Punjab Preservation of Sub-soil Water Act, 2009, enacted by the Assembly. The effective implementation of this Act did postpone the extraction of groundwater from May 15 to June 15 — a very hot and dry period during which there is a very high level of evapo-transpiration.

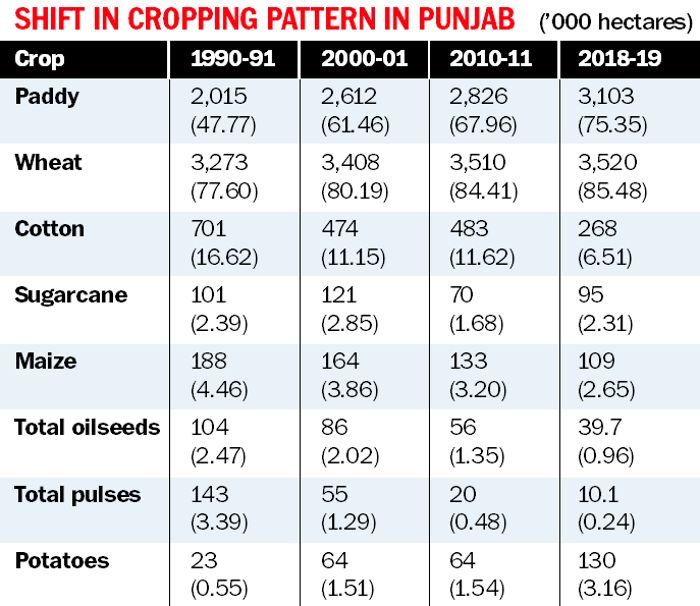

The Vidhan Sabha panel’s report is not the first to highlight the depleting water table and impending water scarcity. Some expert committees and several experts have been pointing to the unsustainable overexploitation of groundwater since the mid-1980s. Johl Committee-1 (1986) and II (2002), constituted by the state government for restructuring and diversifying agriculture, made significant recommendations for shifting a substantial area (20 per cent) from under paddy, but these did not cut any ice. Instead, the area under paddy increased from 3.9 lakh hectares (9.62% of the net sown area) in 1970-71 to 31.03 lakh hectares (75.35% of the net sown area) in 2018-19. The Draft Agricultural Policies (2013 and 2019) prepared by the Punjab State Farmers’ Commission also recommended crop diversification by shifting a considerable area from under paddy. Unfortunately, these draft policies never fructify into an agricultural policy. Consequently, the state has neither an agricultural policy nor a comprehensive water policy. Even the Punjab Water Development and Regulatory Authority, constituted in 2020, has not included irrigation under its purview. Unfortunately, successive governments of Punjab, instead of acting upon the recommendations of their expert committees, have been indulging in cheap, competitive political populism aimed at vote banks. This is a classic case of irresponsible governance.

Paradoxically, among the major rice-producing states of India, Punjab is the most inefficient in terms of water productivity as it is using 5,337 litres to produce 1 kg of rice, while the all-India average is 3,875 litres (in West Bengal’s case, it is 2,605 litres). Water consumption in total rice production in Punjab increased from 16,642.5 billion litres in 1980-81 to 63,153 billion litres in 2017-18, out of which more than 70 per cent was groundwater. In 1980-81, Punjab exported 81% of its total water (in the form of rice contribution to the Central pool) used in rice production; it increased to 88.46 per cent in 2017-18.

To meet the increasing demand for irrigation, the number of tubewells in the agricultural sector shot up from 1.92 lakh in 1970-71 to 14.76 lakh in 2018-19, an increase by 7.69 times. Compared to it, the net sown area rose from 40.53 lakh hectares in 1970-71 to 41.18 lakh hectares in 2018-19 (an increase by only 1.02 times). The gross cropped area increased from 56.78 lakh hectares in 1970-71 to 78.39 lakh hectares in 2018-19 (38.06 per cent rise). Evidently, the number of tubewells registered a highly disproportionate rise as compared to the rise in the net area sown and the gross cropped area. Consequently, the net annual groundwater availability for irrigation development decreased from 2.44 million acre feet (MAF) in 1984 to minus 11.81 MAF in 2017. Such a dark situation arrived due to overexploitation of groundwater.

Overexploited blocks

The aggregate gross groundwater draft in Punjab increased from 145 per cent in 2004 to 166 per cent in 2017. The number of overexploited blocks rose from 53 (44.92 per cent) in 1984 to 109 (78.99) per cent in 2017. According to the latest report (2019) of the Central Ground Water Board, in 18 of Punjab’s 22 districts, the draft was more than 100 per cent in 2017. Among them, seven districts are such in which the draft is in the range of 208-260 per cent. In another four districts, the draft is 151-200 per cent; in seven other districts, it is 101-150 per cent. Of the remaining districts, in two the draft is 98 per cent and 99 per cent and in another two it is 74 per cent and 76 per cent. The author’s study revealed that during 1996-2016, 12 districts (predominantly paddy-growing) had witnessed a decline in the water table ranging from 3.55 metres to 22.05 metres.

It is quite worrisome that the area where the groundwater table is more than 10-metre-deep has been continuously increasing. It rose from 7.5 lakh hectares (14.9% of total area of Punjab) in June 1989, to 33 lakh hectares (65%) in June 2016 — an increase by 4.4 times over a span of 27 years. Due to increasing dependence on groundwater for irrigation, the electricity consumption in agriculture jumped from 463 million KWH in 1970-71 to 12,484 million KWH in 2017-18 (an increase of nearly 27 times). Significantly, the higher increase has been witnessed in those districts which are predominantly rice-growing.

Lack of awareness

The author’s study (ICSSR-commissioned major research project, 2013-15) has revealed that the level of awareness and sensitivity about judicious and optimum use of water is very low among water consumers across various sectors (agricultural, domestic, industrial and commercial) and the government too is not serious about the emerging water scarcity. Water harvesting and conservation are nearly non-existent across the sectors. Shifting a substantial area from under paddy would require a compatible policy intervention both by the Central and state governments. For optimum and sustainable use of water, Punjab must have comprehensive agricultural, industrial and water policies and effective and result-oriented implementation thereof. All stakeholders must join hands to address the issue so as to save Punjab from approaching desertification.

The author is Professor of Eminence (Economics), GNDU, Amritsar.

Views are personal

Send your feedback to letters@tribunemail.com

Act now to save Punjab on the water front

{$excerpt:n}